The newest issue of the Royal Studies Journal is a special issue on British royal tours of the Dominions, compiled and guest edited by Robert Aldrich and Cindy McCreery (both University of Sydney, Australia). Ten articles discuss several aspects of these royal tours, from the response by Canadian women over the relations with indigenous people to the practical side of royals spending a pretty long time on ships, and many more.

We got together with Robert Aldrich, Cindy McCreery, and Chris Holdridge (University of the Free State, South Africa, and Monash University, Australia) to discuss their ideas for the special issue, the connections of royal studies and post-colonial-studies, and their research.

Cindy McCreery

Chris Holdridge

Cathleen, Kristen, and Elena: Robert, Cindy, and Chris, thank you for joining us for this roundtable on the special issue on British royal tours. Robert and Cindy, you already published books together on royal tours, and I quite well remember our discussions on the topic in Gießen and Madrid in 2017. Chris, you provided an afterword to this special issue – could you all please tell our readers a bit more about the idea behind this special issue, and how it relates to this field in general? Also, what do you see as most influential in the academic field of studying royal tours?

Robert: After reading Amitav Ghosh’s wonderful novel The Glass Palace, I became interested in the monarchs – emperors, kings and queens, maharajas, sultans – who were dethroned and exiled by the British and French. (Exile was a kind of enforced tour!) That led to a book on Banished Potentates. But I had also started to think more generally about monarchies and colonies, and Cindy and I began to work together on that theme, and edited a volume on Crowns and Colonies for Manchester University Press. Cindy’s fascinating research on the global tour of Queen Victoria’s son Prince Alfred suggested that travels by monarchs and members of royal families were part of a more general phenomenon, and that these grand tours provided initiations to international affairs for the royals, examples of ‘soft diplomacy‘ and affirmations of colonial rule. Our edited Royals on Tour (also published by Manchester) explored some of those travels by British, French, Italian and Portuguese royals, and also colonial-era tours by royals from places such as Japan, Thailand, Indochina and the Dutch East Indies. Given the breadth of British empire, and the significance of royal tours to Australia, where we live, Dominion tours was an obvious topic for another collection, and the contributors to our RSJ issue offered many new insights into royal travels in Australia, Canada, New Zealand and South Africa, and on such issues as relations between indigenous people and the Crown, gendered experiences of royal tours, and the role of displays of military might on those occasions.

One of the key academic benefits of studying royal tours is how they provide an example of ‘connected history’ – travels in a real sense link colonial metropoles with colonies, and colonies with each other, as well as linking elites to ‘commoners‘, and Europeans with indigenous people and with settler and diasporic populations. They involved not just an individual ‘tourist’ but many others, from vice-regal officials to servants, performers to spectators. Royals were (and are) celebrities – it is extraordinary that perhaps a quarter of the population of Australia turned out to see the queen when she first toured the country in the 1950s. The visit to Australia later this year of the Duke and Duchess of Sussex may not draw such crowds, but will no doubt create considerable interest. The visit of the young couple will show how the British royal family and monarchy continually reinvent themselves – but also perhaps spark renewed debate on the future role of the British sovereign as head of state in Australia.

Cindy: As well as the influences Robert mentions above, we have been inspired – but also challenged – by much of the work which historians and art historians of early modern Europe have done on royal tours. As modernists who live and work in the global south, we are quite passionate about showcasing modern as well as non-European case studies of monarchical performance such as royal tours. So we want to emphasize that monarchies and royal tours are as much a part of the 19th and 20th (and indeed 21st) centuries as, say, the 16th!

Chris: Monarchy is an important part of the history of imperialism, and an aspect near inescapable for historians of empire. The articles in the special issue show that rather than colonial replicas of the politics of royal display in the British metropole, royal tours and their reception in New Zealand, Australia, Canada and South Africa very much relied on the local politics of these colonies or dominions. It is this attention to local politics that is for me the most stimulating direction in the study of royal tours. Debates about race, such as in Britain over the recent 2018 wedding of Prince Henry to the biracial American and former actress Meghan, Duchess of Sussex, had their much earlier precursors in the colonies. Studying royal tours is an entry point into understanding the long histories of multiculturalism and the complex changes over time to social hierarchies. It tells us a lot about the visibility or occlusion of violent settler colonial pasts and diverse colonial or dominion populations, and the impact of this on the social fabric. If anything then, studying royal tours and monarchy in general should not be a niche field. Histories of empire, and national or global histories, are enriched when we ask bigger comparative questions about the importance and connected histories of monarchy. Royal tours are but one way to go about this.

Cathleen, Kristen, and Elena: Modern royal tours show indeed the worldwide, and world-encompassing, reach and influence of monarchies, especially the British monarchy. The issue highlights the complex issues of empire, commonwealth, royal tours, independence, ceremony, racism, nationalism, colonialism vs anti-colonialism vs post-colonialism, and so on – how do you all deal with studying a subject so intertwined with these issues, which of course are also still political dynamite today?

Robert: Fortunately, royal tours produced much documentation – newspaper reports, commemorative volumes, memoirs and travelogues, images and artefacts. (And, more recently, of course, there are television reports and now internet streaming.) These provide a rich archive, and the tours shed light on many issues in the history of monarchy and in the history of the countries royals visited.

One strategy to try to make sense of it all is to focus on a particular tour and to examine the dynamics of the itinerary and ceremonies, the reception of the royals, and reportage around the visits. Such a fine-grained ‘snapshot‘ allows a researcher or reader to zoom in to a particular time and place. Alternatively, study of a succession of visits shows how change occurred – changes in the way the monarchy presented itself, changes in the circumstances that inspired tours, changes in reactions from the diverse groups in countries that were visited. As the articles in our issue of the RSJ show, yet another approach is to look at particular themes, for instance, the voyage itself, or the experiences of women or indigenous people, or the place of the armed forces and returned soldiers during these tours.

Cindy: Yes, and I think that as historians we need to be mindful and at times quite explicit in our work about linking past controversies with present campaigns. Jock Phillips’ article on the New Zealand Maori and Royal tours, Mark McKenna’s on Australian indigenous people’s relationship with the British monarchy and Carolyn Harris’s on Canadian women and royal tours all engage, albeit in different ways and with different methodological approaches, with issues of racial and gender equality that are very much relevant today.

Chris: There are no easy answers to historical questions about race, the nation, antic-colonialism and imperial loyalism. What makes royal tours so fascinating are the contradictions that one faces when looking at the archivalia that Robert mentioned, whether commemorative pamphlets or newspaper accounts. Looking beneath the surface, jubilant welcomes and warm receptions were often political theatre belying deeper tensions or resentments. In South Africa, as Hilary Sapire argues in her article on the 1925 royal tour of Edward, Prince of Wales, Afrikaners showed a mixture of unease or deference two decades after the end of the South African (Boer) War. Complexities are often best examined through case studies, of which royal tours are excellent examples. One way to tackle these complexities is to read against the grain of press accounts and official versions of events by elites to attempt a recovery of different voices and motivations. We hope that it is clear in the special issue how very different the meaning and possibilities of royal tours were for a white New Zealand immigrant from London compared to an Indigenous Australian or French-speaking Canadian. It is at the micro-level of these different voices that we can then pan out to challenge the often simplified and uniform broader narratives around monarch and empire.

Cathleen, Kristen, and Elena: What I really liked about your special issue in the Royal Studies Journal is the focus on modern monarchy, and the focus on non-European events. The British Empire and Commonwealth was, after all, world-spanning, and had much more influence outside of Europe than in this tiny continent. What is your impression, also as scholars from South Africa and Australia: in what ways do royal studies profit from non-European views, and how influential is European scholarship for non-European research?

Robert: European monarchy is by its very nature a cosmopolitan institution – through dynastic traditions, intermarriage, conquests of territory in Europe and the wider world. In the age of exploration and empire, European monarchies and non-Western monarchies came face to face, sometimes in violent confrontation, and both of these groups of monarchies were changed in the process. European monarchies were imposed on many colonised areas, and European notions of governance survived even after decolonisation in some countries. Malaysia, for instance, has a Westminster style of parliamentary government, but a particular sort of elective monarchy (with the head of state selected for a five-year term from among the hereditary sultans). The monarchies of countries such as Thailand underwent a wide-ranging modernisation in part because of their contact with the West; this can be seen in transformations in political institutions and court ceremonial, and in personal links developed, for instance, by the late nineteenth-century King Chulalongkorn and his monarchical peers in Europe. To understand modern monarchy, therefore, research on European and non-European forms of dynastic rule are complementary, and those strands of historiography need to be brought even closer together. There are useful comparisons to be made, for instance, between the sacred nature of European and non-European rulers – the divine right of old regime monarchs in Europe, Buddhist kings as devarajas, Confucian rulers as ‘sons of heaven‘. The ‘new imperial history‘ tends to view the colonising and the colonised countries within the same field, and studies of modern monarch may also profitably reflect on the transnational and global histories of Western and non-Western monarchies in the colonial and post-colonial age. We need greater dialogue between specialists of European monarchies and those in Asia, Africa and Oceania in order to discuss the long-lasting effects of the cross-cultural encounters of different royal families and their traditions.

Cindy: In response to your point above, I actually think that the British Empire and Commonwealth was pretty influential in Europe as well as beyond it. If you think about, say, French, Belgian and German nineteenth-century colonisation schemes, many of their greatest advocates were inspired by the British model. And of course Belgian and German monarchs (notably Leopold II and Wilhelm II) were notorious for their determination to build empires to rival those of Britain… So I think that looking at these overseas empires is absolutely essential for improving our understanding of the European monarchies themselves. European scholarship on monarchy is very important – e.g. David Cannadine’s work on representations of the British monarchy at home is really helpful for understanding their representations in colonial Australia, which built on existing British representational models. I also think that Europeanists benefit from considering scholarship on non-European examples, whether that be responses to European royals in Asia, responses to Asian royals in Europe – or in their home countries.

Chris: I agree with what Robert and Cindy have mentioned. Global history has been one of the great benefits and spurs to new scholarship, bringing into conversation historians of early-modern Europe, for example, with historians who work on Australia, South Africa or India. These comparative conversations have always been present, but there is a renewed energy of late for global comparisons. One of the challenges, however, is to avoid an assumption that Europe brought its models of monarchy, governance, trade and ideas in a one-way flow to the rest of the world, or that unique extra-European cultures can be categorised into European models. This is what the postcolonial historian Dipesh Chakrabarty referred to as the need to ‘provincialize Europe’. Modernity is not a European invention, progress is not the preserve and responsibility of Europe, and monarchy and democracy are not necessarily European exports. Empire was a process of exchange—frequently violent and unequal—when Europe encountered societies that had their own advanced social orders, hierarchies and dynasties.

Comparison can help us better understand these complexities of monarchy. Two books by historians based in the global south come to mind as excellent examples of this approach. The first, Milinda Banerjee’s The Mortal God: Imagining the Sovereign in Colonial India, was published this year by Cambridge University Press. It is an intellectual history of the princely states in India and debates and exchanges with British imperial power over what constituted the sovereign and their authority, debates that often involved elites and peasant contesting what Banerjee terms the ‘political theology’ of monarchy. The second book, now two decades old, Terrific Majesty: The Powers of Shaka Zulu and the Limits of Historical Invention by Carolyn Hamilton, demonstrates that the Zulu King Shaka is an invention of the colonial archive, historical accounts and popular memory that relied on European conceptions as its foundation. This is an invention of Shaka’s greatness and infallibility that served as a useful foil in British imperial propaganda as much as it still serves as a central component of Zulu identity and nationalism in South Africa today.

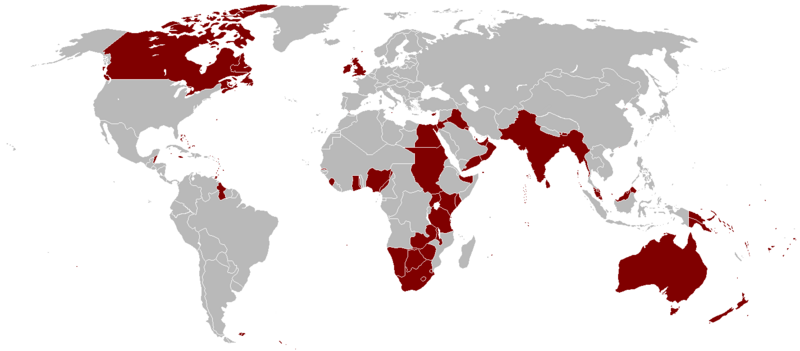

The British Empire in 1921

The British Empire in 1921

Cathleen, Kristen, and Elena: Now, this is a call to arms the books for us historians! Include research and researchers from the Global South! I can also only emphasize this: I worked with Milinda Banerjee on nationalism and monarchy, and his insights as a scholar based in the Global South, but also trained in Europe were enlightening. As you might know, most of our readers are researchers of premodern periods in which there were also royal tours. Can you tell us a bit how they would compare to modern royal tours? Was it ‘just’ a change of technology and infrastructure regarding transport and media coverage, or can you pin-point some more substantial changes as well? What about the change of royal families from active rulers of their own dominions to representatives for their states, to what degree does this change play a role? In this aspect, how important is the role of ‘performance of monarchy’?

Robert: The pre-modern tours and ‘progresses‘ of monarchs provided templates for later travels, but certainly the new technologies and the expansion of empires were key differences between those travels and those in the age of empire. There are, however, other differences. By the late 1800s and early 1900s, most European monarchs were losing, or had lost, the absolute powers enjoyed by their forebears; overseas travels provided a new way to sustain and indeed re-establish their place in the nation, and to present themselves as sovereigns over ‘dominions beyond the seas‘. Empire provided an opportunity (indeed a need) for rulers such as the British monarchs to affirm their special ties with settler populations – and there is an element of ‘race patriotism‘ in this sense – but also their paternalistic imperium over colonised people of very different ethnic, religious and social backgrounds. Colonies presented the possibility for ‘performing monarchy‘ on a global stage, and to use such performances to promote empire at home. The incorporation of the Kohinoor diamond (the subject of a fascinating recent book by William Dalrymple and Anita Anand) is one manifestation – the diamond was effectively taken as war booty after the British East India Company annexed the Punjab and deposed its ruler, who then lived in exile in Britain as a sometime wayward protégé of Queen Victoria. The diamond taken from him was incorporated into the British crown jewels. When it was set into the crown of Queen Alexandra – who as the consort of King Edward VII was also Empress of India – she was, in a literal sense, wearing the empire on her head. The ways in which the colonies were intertwined with the history of modern monarchy in Europe is an often overlooked aspect to their evolution, and we hope that our research and that of our collaborators has shed light on the place of overseas empires in the construction of modern monarchy.

Cindy: Yes, and I think another important element of modern royal tours is the way in which they frequently reflected the huge economic, political and cultural significance of the colonies – and colonists – in the overall empire. When the Duke and Duchess of Cornwall and York travelled around the British empire in 1901, they paid enormous attention to making sure that each colony they visited felt special, as if it was THE most important stop on the itinerary, and they spent hours shaking hands with local veterans of the ongoing war in South Africa. While they were greeted with great courtesy and honour wherever they went, there was also a sense that the colonists DESERVED this royal visit, and that such tours were now a royal duty. So the focus on satisfying the broader public, rather than say just elite audiences, probably marks a substantive difference from early modern royal tours.

Chris: Of course, as you mention, the most dramatic change over the past two centuries has involved travel and communication, in the move from sailing ships to steam power and from the printing press to the telegraph, radio, television and then the Internet. Travel times diminished greatly, and so did the dangers for royals travelling to distant colonies. This made the option far more attractive by the late-nineteenth century. To echo what Cindy has said, there was an expectation in the rising mass societies of this era that the authority of politicians should be seen, whether these were presidents or monarchs. Increased literacy and a more active public resulted in a demand to see royalty as part of the political fabric connected to and answerable to ordinary folk. And media thus transformed the reception of royalty on display as a democratised and even celebrity event that drew in a larger audience through print or on screen. Royal pageantry thus became more democratised in its wider audience beyond courtly display, to the streets of the capital and the outer reaches of empire.

Cathleen, Kristen, and Elena: Thank you for these further insights into the complex topic of royal tours, and how studying them profits us in understanding monarchy, be it modern or premodern. One last question to you all on royal tours: do you have any favorite anecdotes of royal tours you’d like to share? Or, can you recommend any additional media (images, newspapers, video, speeches, radio broadcasts, etc.) for anyone interested in modern royal tours?

Robert: Some of my own favourite anecdotes come from the travels to Europe of Asian monarchs – the king of Cambodia, Sisowath, in visiting Paris in 1906, for instance, brought with him a group of Khmer dancers.

The young women so intrigued Rodin that spent hours sketching the dancers, and even followed the troupe from Paris to Marseille to continue drawing them. King Sisowath meanwhile enjoyed shopping in Paris, and gave a royal medal to the manager of one department store he patronised! Such anecdotes show the personal side of royal tours, but also how they provided occasions for two countries to ‘discover‘ each other.

There are a number of commemorative volumes on royal tours, and museums sometimes put on display artefacts from these travels. The British Film Institute’s website, among others, has interesting documentary footage, and it is possible to find reports on other tours on YouTube. Royals were always photogenic, so newspapers and other illustrated magazines of the time are also full of images and accounts – the modern phenomenon of royal paparazzi owed much to royal travels.

Cindy: One fun anecdote from Prince Alfred’s 1867-8 tour of Australia comes during his visit to the Hunter River region of New South Wales. A crowd of local people wait patiently for hours on the riverbank to watch him pass by on his steam launch. By the time the boat comes into view it is midday and the hot Australian sun, reflecting off the shiny paintwork of the royal launch, creates such glare that the spectators really can’t see very much. ‘Mrs Windeyer’, a middle-aged woman who was married to a prominent local landowner and later campaigned for women’s suffrage, describes the scene in a letter to her daughter-in-law, explaining that ‘I did not see Prince Alfred but he may have seen me!’ I think that beautifully sums up both the loyalty of many people in the nineteenth-century British empire but also their ongoing sense of individual pride and self-worth. The Prince wasn’t the only person worth looking at on that hot day!

Chris: A memorable moment is when Queen Elizabeth II visited South Africa in 1995, following the election of Nelson Mandela as president the year prior. The Queen had last visited South Africa in 1947 with her father King George VI, her mother, and Princess Margaret. During the majority of the time between, Mandela had languished in prison for 27 years under the oppressive apartheid regime. Unlike when her father greeted onlookers in 1947 as head of state when South Africa was still part of the monarchy, in 1995 a black man with the office of head of state of a republic, and equally as regal in appearance as his British counterpart, stood next to the Queen. The contrast of a half-century was telling. The New York Times published a short but poignant ‘Cape Town Journal’ of the Queen’s visit. While many—especially black—South Africans saw the Queen’s royal tour as evidence of the end of South African isolation within the world and the possibility of a better life, others were more circumspect. One 64-year old coloured librarian, Vincent Kolbe, recalled waving a flag when a teenager in 1947 at the royal entourage. As he said to the New York Times reporter, “When you get old, you get nostalgic. This is like revisiting a moment in your life… But there isn’t the same kind of devotion now as there was then. She’s somebody else’s Queen now.” In my own memories of 1995 as a then nine-year old, I recall far more strongly South Africa’s victory against New Zealand in the Rugby World Cup final, and the moment Nelson Mandela lifted the trophy with the team captain, than I do the visit of Queen Elizabeth II!

1995 in South Africa

Cathleen, Kristen, and Elena: Now, sports, power and national identiy is also quite the interesting topic! Finally, what can we expect next from you?

Robert: Cindy and I are now putting together an edited volume on monarchies and decolonisation in Asia, looking at both European colonial monarchies and Asian ones. This is part of a larger project, with several collaborators in Australia and overseas, on the general topic of monarchies, decolonisation and royal legacies. Meanwhile, I’m finishing a book with a geography colleague in Sydney, John Connell, for Palgrave Macmillan, that looks at several dozen places around the world that did not become independent countries – we published a volume called The Last Colonies twenty years ago, and we are looking at those places once more. Monarchy does figure in the story. After all, Queen Elizabeth still reigns over islands and enclaves from Bermuda to St Helena, from Gibraltar to Pitcairn. The king of the Netherlands reigns over six islands in the Caribbean, and the Danish queen rules over the Faeroes and Greenland. And after that, I’m writing a general book on European colonialism since 1800 with a Swiss scholar, Andreas Stucki, for Bloomsbury Publishers.

Cindy: I am currently writing a book on Prince Alfred’s world tour in the 1860s and 70s, which I describe as the first global royal tour. I am also planning a second article on the 1901 royal tour – there is so much more to say about it! – which will examine representations of race and gender in the tour. I am also planning a conference presentation on the royal tours of King Kalakaua of Hawai’i and Sultan Abu Bakar of Johore – two other nineteenth-century keen royal tourists. Robert and I are teaming up with our colleague Mark McKenna (who contributed an article to this special issue) to plan a possible museum exhibition on monarchy in Australia. Watch this space!

Chris: Besides finishing a book on settler protest and the end of convict transportation in the British Empire, I am collaborating with Wm. Matthew Kennedy on the book Captive Subjects that looks at the thousands of prisoners of war sent to India, Ceylon, Bermuda and St Helena during the South African War. Issues of sovereignty and subjecthood abound, and I have become increasingly fascinated by the post-Napoleonic history of exile to St Helena. Besides 5,000 interned Boer prisoners at the turn of the twentieth century, the British exiled the Zulu king Dinuzulu kaCetshwayo to the island in the 1890s. Boer POWs—most ardent republicans and some racist—did not take kindly to news that the Zulu King received better treatment and hospitality than they did! Like Robert, I have thus been drawn to the history of royals in exile, which is an interesting counterpoint to royals on tour.

Cathleen, Kristen, and Elena: Again, thank you all for indulging us with this interview; and good luck with your respective projects! We’re looking forward to reading them, or seeing a bit of them (in the case of the exhibition)!

Robert Aldrich

Robert Aldrich